Earl Wild Plays Liszt In Concert (Only CDr’s available)

Earl Wild Plays Liszt In Concert (Only CDr’s available)

Couldn't load pickup availability

Please note this is sold out but CDrs are available for purchase. Order Here

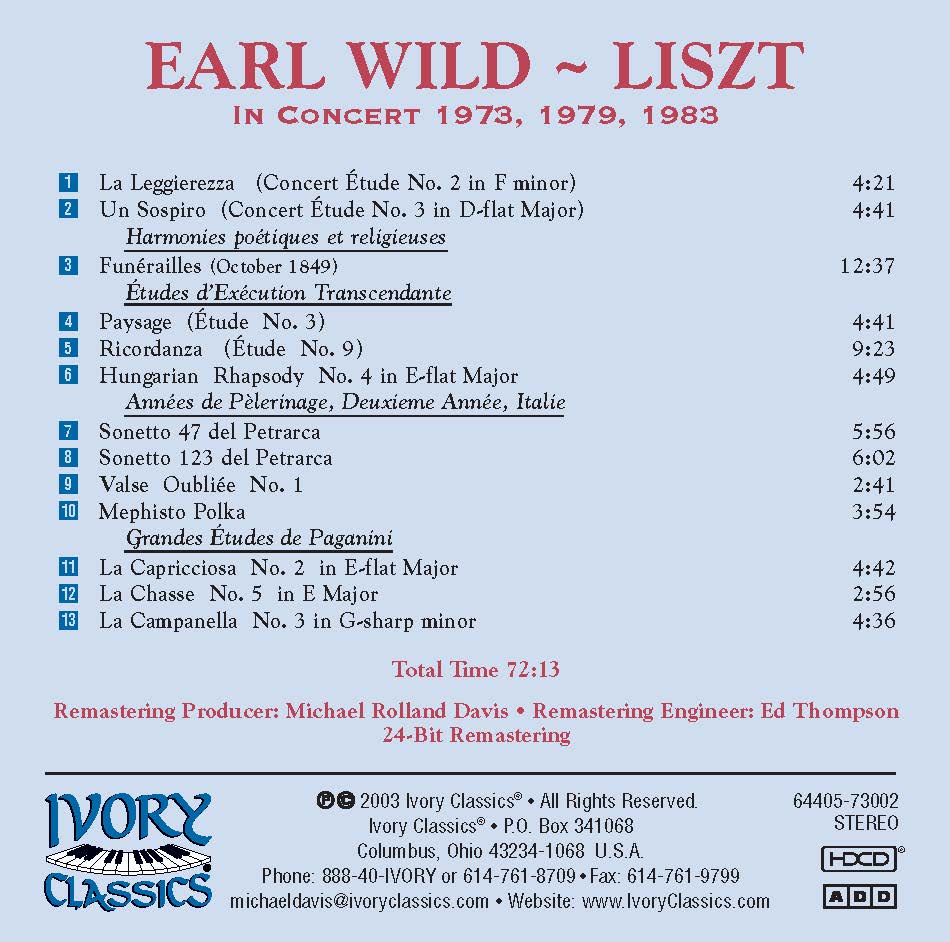

Introducing Earl Wild Plays Liszt In Concert 1973, 1979, and 1983, featuring the critically acclaimed pianist's mesmerizing performances. These recordings are the perfect blend of skill and passion with pristine sound quality that brings you closer to the artist. Experience a melodic journey through the legendary performances of Classics like Liebestraum and Mephisto’s Laugh.

Earl Wild Plays Liszt In Concert 1973, 1979, 1983

Franz Liszt (1811-1886):

Piano: Earl Wild

Producer: Michael Rolland Davis

Engineer: Ed Thompson

Total Time: 72:13

Piano: Bosendorfer, Baldwin

EARL WILD plays Liszt In Concert 1973, 1979, 1983 -- (High Definition Compatible Digital) recording.(ADD)

Continuing the recent Ivory Classics releases of live - In Concert Earl Wild performances, we now present this new disc consisting of all solo piano pieces of Franz Liszt. All pieces are taken from the material performed in recitals from London - 1973, Chicago - 1979, and Tokyo - 1983. Earl Wild, the legendary 87-year-old Grammy award-winning dean of pianists plays the music of Franz Liszt like no one else. Super virtuosity and romantic elegance make this truly a disc to own and treasure.

Review

For once the description, 'the last of the great Romantic pianists' is surely accurate. -Gramophone, October 2003

This is the disc to own if you're looking for an introduction to Earl Wild and Liszt. - Fanfare, Sept./Oct. 2003

Wild is a pianist of superhuman bravura and achievement. Difficult to imagine a performance more scintillating.

-Gramophone, October 2003

This disc constitutes a veritable feast for admirers of Earl Wild. All the performances were recorded live in London (1973), Chicago (1979), and in Tokyo (1983) and none has been released before. The program is a Wild specialty, Liszt, and the means at his disposal: a quicksilver, dramatic, leonine control over rhetoric, a big, burnished malleable tone, and an incisive command of structure. This suits very well as a description of his mature playing of the B minor sonata – a piece not here - though we have more than one example of his way with it on other Ivory releases. Instead, we have more than enough to demonstrate quite why he has been held in such esteem – and awe – these many years. I should sound a mild cautionary note about the recording quality from these venues first; there can be a clangourous sound that, very occasionally, leads to climax distortion. But I should add that these are, by and large, rare moments and I can guarantee that, so swept up will you be in some incendiary music-making, that you won't notice, still less care.

Let's start with La Leggierezza in this extrovert, propulsive, and intoxicating reading. Yes, maybe he can push the rhythm in his driving torrent but just listen to the brilliantine treble, the stunning technical resource, and also the interpolated (Wild composed) coda, a witty sign-off in the tradition of Leschetizky. Such leonine magnificence is heard in Un Sospiro the changing performances of which the assiduous Wild collector can trace back to a 1946 Stradivarius LP and thenceforward to Etcetera LPs and CDs in 1987 as well as a Pearl disc from 2000. Funérailles receives a high wire and unremittingly virtuosic traversal, magnificently contoured and strongly rhetorical with an intensifying screwing up of tension. It's only slightly vitiated by a somewhat clangy piano attack, as preserved in the recording, which can blunt the ultimate transmission of that level of tension and power. For a more nuanced and less Krakatoan performance try the Quintessence LP of the late seventies or the Etcetera discs already cited. But there is really very little to quibble with here, even given the octane frenzy Wild exhibits with such panache. It's a slight shame that Paysage ends so abruptly – leading me to speculate an instant outburst of applause (it does slightly break the spell) – and whilst Ricordanza isn't quite note-perfect, should such considerations trouble you, it has a truly noble poeticism throughout.

The Valse Oubliée No.1 is full of flighty wit and coloristic skill and depth. There's some tape hiss in La Chasse but such is the dramatic incision of the playing on offer, so reverberant are the flourishes, that one feels oneself in some huge Vulcanic forge scorched by the energy of the pianism. The two Petrarch Sonnets are examples of super-Romanticism in action; more ascetic listeners might find these and the recital as a whole too much red meat but one always finds that Wild is ultimately on the side of the Angels and generally doesn't go in for trick inflations, texture thickenings or the like. For readers who may blanch there are always the rather more measured studio recordings; in the case of the Sonnets for instance go to Etcetera for No.47 and to a multiplicity of sources for No.123 – I'd recommend an EMI disc of 1973 if you can get it or the Quintessence LP of 1978. Such is the bravura of the playing that avenues like this open up all the time.

Strongly recommended then to Wildeans: to them goes the bravura, to them the poetry. Sober sides may want to dip in first. Prepare to be gloriously singed.

Jonathan Woolf, Music Web.com, Apr. 2005

Writing of Earl Wild's Liszt recital at the Queen Elizabeth Hall in 1973, I noted how the notes cascaded like diamonds from his magisterial fingers. And revisiting some of those performances, together with others from Chicago in 1978 and Tokyo in 1983, reinforces the impression of a pianist of superhuman bravura and achievement.

Wild gives new meaning to the title of Liszt's second concert Study, La leggierezza, and to it's a capriccio instruction. His performance concludes with a dizzying coda of his own invention (a fleeting romantic gesture as the sleeve note put it), an extension, as it were, of Leschetitzky's ending beloved of Paderewski and Moiseiwitsch. Such gestures are part and parcel of Wild's romantic freedom and authority, his willingness to fill out the harmony here, add a sumptuous counter-melody there (Petrarch Sonnet 123) or ornament Liszt's skeletal outline so typical of his later works (Mephisto Polka).

For Wild, like Liszt himself, the text is hardly sacred but an opportunity for recreation on the grandest scale. Again, like Liszt, Wild is hardly the sort of pianist to hide aristocratically behind his blistering technique which he displays with an unbridled ferocity - even in such relatively lyrical effusions as 'Un Sospiro', 'Paysage' or 'La Ricordanza' you feel it could blow the music apart - and the pressure rarely lets up. A nervous brio plays across such pages like some all-powerful jet. As for the Fourth Hungarian Rhapsody, it world be difficult to imagine a performance of more ardent or scintillation bravura, or of fingers and wrists impacting with a more visceral force, or of a display in the final friska of feather-like octaves - brilliance which others can only contemplate, as it were, from the wings.

The bass notes of Wild's Bosendorfer ring out with unparalleled splendour in Funerailles, the Mephisto Polka is even more daunting and acidulous than on his legendary disc 'The Daemonic Liszt', and in the second of the Paganini Etudes his technique leaves scorch marks on the score; even Horowitz (a great admirer of Wild) finds this hard to match.

As piano playing this is phenomenal. The recordings have come up excellently and are lavishly presented and would urge all collectors of unique high-wire mastery to hear his Liszt disc. For once, the description 'the last of the great Romantic pianists' is surely accurate rather than hyperbolic.

Bryce Morrison, Gramophone, Oct. 2003

Actually, the complete title is "Earl Wild plays Liszt in Concert." These recordings were made of the artist in recital in London (1973), Chicago (1978), and Tokyo (1983). All have been beautifully remastered and balanced by producer Michael Rolland Davis and engineer Ed Thompson.

There is good reason to release live recordings by concert pianists - and no one repays the effort better than Earl Wild does. The spontaneity that comes when a pianist is communicating with a live audience may be lost in the recording studio, where it is now possible to "patch" a troublesome passage in the digital editing to a degree that was unimaginable in the era of tape recording - in the interest of ever-elusive perfection. But note-perfection was not necessarily the highest of pianist virtues for Franz Liszt, and it need not be for us.

Having said that, I would like to issue a minor complaint against the practice, followed by all the record labels today, of following each selection in a live program with a snippet of audience applause. It's as if the producers were motivated by twinges of guilt in calling our attention to an audience presence of which we may not have been aware. When I am really into hearing a compelling performance, I don't give a damn whether it was recorded live or in the studio. For purposes of home listening, audience applause is an intrusion, and therefore an annoyance.

Over the years, critical ink has mostly been spilled on Earl Wild for his demon technique, to the exclusion of his interpretive powers. But no one can take you quicker to the heart and soul of Franz Liszt than he does. The program presented on this CD includes selections from the Transcendental Etudes, the Years of Pilgrimage II: Italy, and the Paganini Etudes - all vintage Liszt. It also includes Hungarian Rhapsody No. 4 (And what's a Liszt recital without at least one of the Rhapsodies?), plus such charmers as La Capricciosa from the Paganini Etudes, portrait of a temperamental prima donna in tricky chain octaves, and Ricordanza (Souvenir) from the Transcendental Etudes, which Busoni likened to a packet of yellowed love letters. In some of the more intimate pieces such as Un Sospiro (A Sigh) and Sonetto 123 del Petrarca from the Italy set ("I beheld on earth angelic grace"), I find Wild's attack a trifle sudden and hard for the material. And the sound of distant church bells in La Campanella seems rather aggressive in this pianist's interpretation.

But he really comes into his own in the Funerailles (Funeral Ode), which is the emotional deep-water mark of the program. In this altogether remarkable piece, heavy chords evoking the tolling of church bells and the low, muffled roll of drums seem to hang ominously over the piano. Wild's is the most compelling account I can remember of this work since Alfred Brendel played it in Emory University's Cannon Chapel some ten or twelve years ago. Liszt wrote the Funeral Ode, subtitled "October 1849," to commemorate three of his friends who were killed in the Hungarian Revolt. It was not, as is often supposed, a memorial to Chopin, who coincidentally died later that month, although Liszt was inspired for the "cavalry charge" in the Ode by a similar passage in the Polish composer's A-flat Polonaise. Here, the applause at the end is really intrusive, for Funerailles really ends, not with the final note, but with the full rest following it.

But don't be put off by my occasional carping. There are certainly enough great moments in this program to qualify it as choice "desert island" Liszt.

Classik Reviews, Oct. 2003